If you have received treatment within our office, and been prescribed at-home exercises, then you may have heard one of the doctors prescribe an “RPE” scale to manage the intensity of exercises and not repetitions. Why? And, what in the name of Arnold Schwarzenegger is RPE?! Well, let’s dive into the deep end of the pool and find out.

Counting “reps” for exercises seems almost as set in stone as having to perform the movement to exercise. For most individuals who were taught the basics of weight lifting and exercise, learning to count how many reps of an exercise that you do happens as early as tee-ball or Little Tyke Soccer. Repetitions of an exercise are a terrific and objective manner to count how much work has been done with a specific movement. Most of all, it is tremendously easy. As long as you know how to count and can then match to the movement you are performing, you can count your repetitions.

What is the RPE Scale?

The original RPE scale was set up by Gunnar Borg in the late 1970s and 1980s in an attempt to give self-perceptive estimates for the patient’s going to cardiovascular rehabilitation. While it seems complex, it is genius and I promise it is quite straightforward and helpful. Unlike most numerical scales the RPE scale doesn’t begin on 0, 1, 10, or even 100. It begins on “6” and ends at “20”. Reporting a “6” on an exercise or workout would mean you felt you did little to no work at all, or very, very light work. Reporting a “20” would mean that you felt it was your absolute maximum and there was no way possible for you to push harder without passing out or causing serious damage to your body. Generally, we shouldn’t be in either category while working out, but rather somewhere in the middle.

This might appear confusing at first. However, when you read Borg’s research further, you see this scale is set as such because it also gives you an easy and fairly accurate way to determine your own heart rate. To do this, you simply multiply whatever number you feel you are on the scale, during exercise by 10. For example, if you were running and stated you felt you were around 12/20 exertion, your heart rate should be around 120 beats per minute (12 x 10 = 120 BPM). 15/20 would be around 150 beats/minute, 8/20 would be 80 beats/minutes, and so on. The Borg RPE scale is quite handy if you are trying to monitor your own heart during activity.

Why We Use the Modified RPE Scale at New Leaf Chiropractic

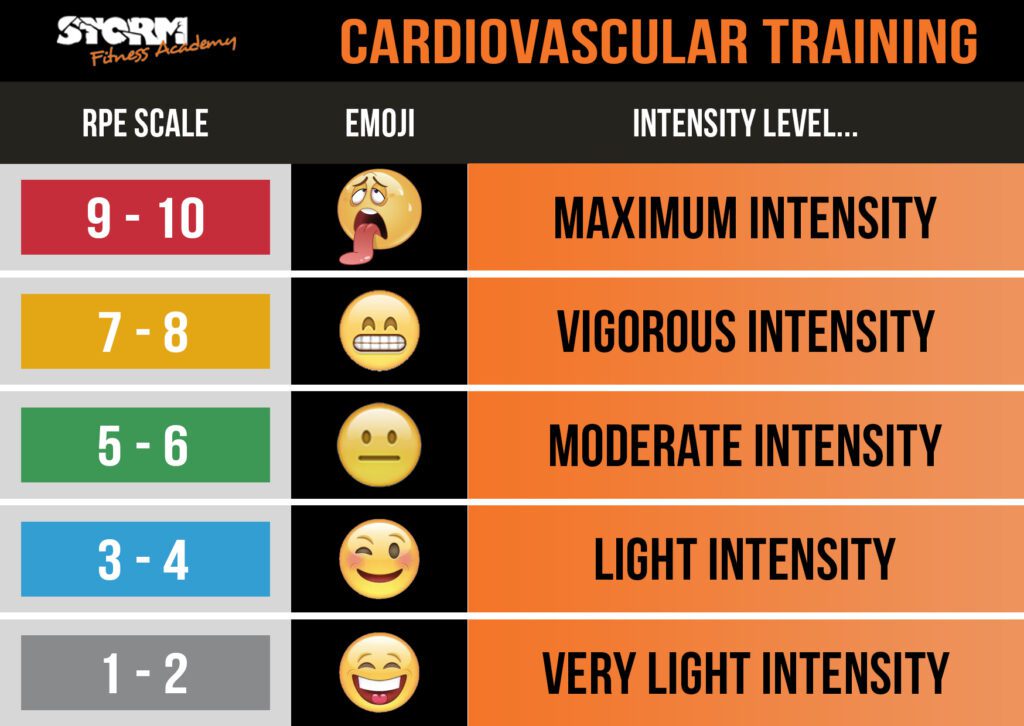

When using this method within the office, we generally employ the Modified Rate of Perceived Exertion scale. Why? Because we believe it is easier to follow. The scale measures from 1-10 with 1 being very, very light or no work, and 10 being the absolute maximum. On the Modified Scale, “1” would be equivalent to “6” on the original scale, and “10” would be equivalent to “20” of the original Borg scale.

Why do we sometimes deviate from an objective measure to exercise that is commonly known and easy? It comes down to relative fitness and how the patient we are working with at the time views their rehabilitation exercises and injury recovery as a whole. For example, let’s say:

- “Patient A” is an elite 5,000-meter runner, who has the Olympic standard time and will be representing her country this year in the upcoming Summer Olympics Games in Tokyo. She is very fit, runs between 60-90 miles per week, has a regimented diet has a sports counselor to address her mental state, has planned out how she will recover, and does performance based weight training several days a week to help stave off future injuries. She has good sleep hygiene (dark room, quiet, cool in temperature, and no screens). Patient A has everything she needs as a professional athlete to perform at her peak potential.

- “Patient B” was at one point in time a high school level athlete and kept general levels of good fitness. He typically works out at the gym 1-3 days a week and stretches about 10 minutes as a warm-up. He goes on a walk or a hike on the weekend that averages 3-5 miles. He eats large volumes of food, with some of it always being piled on with minimal greens on the plate. Patient B drinks borderline excessive amounts of alcohol with friends on the weekends and stays out late. Because of these late nights, he tends to have to fight to normalize his sleep schedule throughout the week for work. His sleep schedule normalizes around Thursday, just in time for another binge weekend to start anew.

Let’s now compare these two patients in a thought experiment. What if both experienced a calf strain? At New Leaf Chiropractic, we help rehabilitate injuries with exercise. If each patient were asked to perform 4 sets of 15 repetitions of single-leg calf raises/eccentrics (heel drops) for strength, with no added weight or assistance, who do you believe would feel as if they had a bigger workout from the exercise? Numerous factors are involved, but in most cases, Patient B is going to feel the post-exercise effects of this set and repetition scheme much more than Patient A. In other words, we have approached Patient B’s exercise capacity and we have barely touched Patient A’s exercise capacity. Because Patient B’s tissue was working harder, relatively speaking, his tissue will adapt to that stimulus. With these parameters, Patient A will not. In this example, we have not given her enough of an outside stimulus for her tissues to adapt.

As you can see, the Rate of Perceived Exertion is very handy. We can give both Patient A and Patient B a target RPE of 4-6 (Modified Scale) when they perform their exercises. Because each individual is basing their RPE off themselves, intrinsically, they should find enough of a stimulus from the exercise to stimulate remodeling of their tissue. In this manner, they can both add appropriate workload to their respective injured tissue with less worry of irritating the

Borg, G. (1970). Perceived exertion as an indicator of somatic stress. Scandinavian Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 2(2), 92–98

Borg, G. (1892). Psychophysical Bases of Perceived Exertion. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise: Volume 14 – Issue 5 – p 377-381